Igbo Landing Be Like, “They Would’ve Had to Kill Us Too!”

When we see or read about the horrors of slavery and say, “they would’ve had to kill me,” the Africans who resisted at Igbo Landing on St. Simon’s Island be like, “I FEEL YOU!”

In May 1803, a ship full of black folk who had been kidnapped from Nigeria arrived in Savannah, Georgia to be auctioned and sold. Before coming to America, they were called Igbo people (also called Ebo/Ibo). That’s the tribe they belonged to. Like The Wanderer and The Clotilda, this was an illegal voyage. In 1798, the state of Georgia made it illegal to bring Africans to Georgia to be enslaved. Slavery was still legal; you just couldn’t bring any new ones over here. They did anyway.

Two white men, John Couper and Thomas Spalding, bought 75 of them to work on their plantations on St. Simon’s Island (which is about 80 miles south of Savannah). Loaded ’em onto their own small ship and took off to St. Simon’s. On the way there, the Igbo plotted. I imagine them talking to each other in their native language, none of the white men aboard knew what they were saying, and they made a plan. What they were not about to do was to continue living as the property of white men. They had survived the ride across the Atlantic Ocean and witnessed the tragedies during that journey. They saw what happened in Savannah. And now they had a chance to escape whatever life was gon’ look like on St. Simon’s.

The Igbo took control of the ship and drowned the white men.

Couper and Spalding weren’t on the ship. I’m assuming they were wealthy plantation owners who preferred to keep their hands clean. So they probably selected and paid for the 75 Igbo they wanted then rode home separately. This is my guess. In the process of stealing the ship and drowning the captors, the boat crashed and sank in Dunbar Creek. They formed a line and marched into the water where most of them drowned. Fourteen of them survived, however.

Black folk who live on St. Simon’s and Brunswick today call that creek Igbo Landing. And there’s a mural in Brunswick on the old Wigfall building on Albany Street, catty-cornered to Ahmaud Arbery’s mural. I visited in February 2022. I was hired as a visiting artist at a private school on St. Simon’s. While chilling in my hotel room one day after teaching, I saw a post on social media that it was the two-year anniversary of Ahmaud Arbery’s murder in Brunswick, Georgia. That was less than 10 miles from my hotel room. I didn’t want to see where it actually happened. So I went to the mural instead. (And shoutout to the community for getting a Black man who was also a native of Brunswick to paint it.)

Click here to watch my 1-minute video of Dunbar Creek and the Igbo Landing mural.

While at Ahmaud’s mural, I saw the painting of Igbo Landing. Before GPSing where Dunbar Creek was, I already knew. It was right around the corner from my hotel room. And every time I passed it, I got a heavy feeling in my spirit. Once I GPSed it, it confirmed that feeling to be true. That’s exactly where it happened. Dunbar creek is a narrow strip of water that you’d easily overlook. People drive over it everyday on their way to work, home, school, etc. Much of Dunbar Creek runs through private residential areas, which is where I was when I decided to snap a picture and video real quick, and Glynn County’s wastewater plant lies just down the creek. No permanent marker acknowledging what happened exists on the banks of the creek or anywhere else on the island.

It’s on us to remember Igbo Landing.

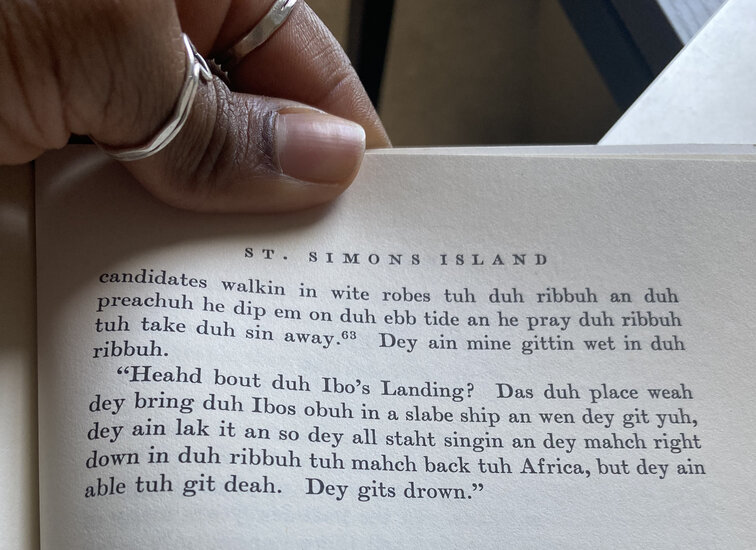

In one of my favorite books, Drums and Shadows, which inspired Krak Teet, St. Simons resident Floyd White in his brilliant Geechee tongue retold the story of the Igbo Landing to his interviewer around 1940.

We have to honor it in our own ways, kinda like how Beyonce paid homage to Igbo Landing in her video for “Love Drought.” A screenshot of that video is the featured image for this article. There are also a number of folktales, which people create to entertain themselves, yeah, but also to gather a sense of understanding for something that’s either too traumatizing to dig back up or too difficult to understand. The story for Igbo Landing is that they flew back home to Africa.

The moral of the story, regardless of how you tell it, is that they resisted slavery. They refused it. They should enter the conversations that include Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman, the 1811 revolt, the Maroons, etc. Because, when we see or read about the horrors of slavery and say, “they would’ve had to kill me,” the Igbo be like, “I FEEL YOU!”

“The Igbos showed that death from rebellion is better than a life of enslavement. They live on in that spirit of activism, in that choice. Resistance to oppressive systems should be celebrated. It is past time to give Igbo Landing the recognition it deserves.” —Ramenda Cyrus

Much love to our new and recurring monthly patrons:

Jessi, June Johnson, Yolanda Acree, Cala, D. Amari Jackson, Yvonne Carter, Black Art in America, Nakia Morgan, Yeseree’ Robinson, Akeem Scott, Rosa Bennett, The Culturist Union, Keya Meggett, Rebekah Hein, Add your name here

Your monthly contributions allow us to pay black writers and artists, and get more creative and consistent in the content we deliver. We put a lot of time, love, and money into researching, writing, and sharing. Click here to learn more.