A Cultural Look at Black Folks’ Views on Their Chi’ren Being Artists

Less these days, but, more often than not, black parents didn’t care for their children going off to college to take up art. Or deciding against school for art or adventure. That was a hobby, not a career. Some defied their parents’ wishes and obtained BFAs and MFAs anyway. Others went the route that their guardians chose then swung back around later in life to do as they wished to begin with. Then there are those who never got back to their love of painting, sculpting, photographing, dancing, designing, writing, wandering, etc.

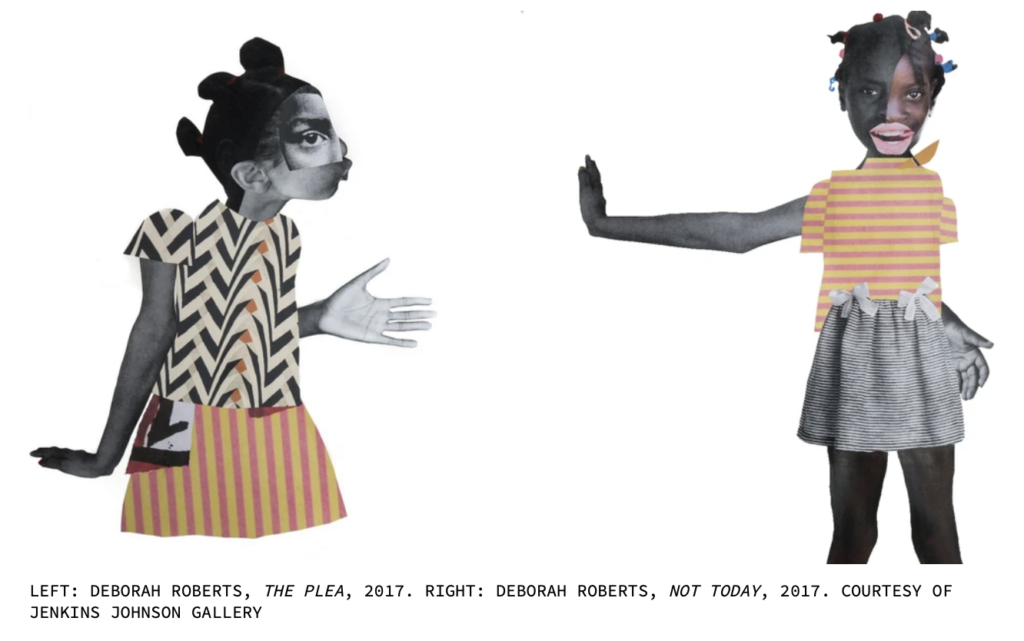

Black people, all over the African diaspora, gotta death grip around their belief in higher education and real jobs. It reminds me of the time my father asked me, after I’d published my second novel, “When you gon’ write a real book?” Although my novel with its 200-something pages, front and back cover, and ISBN number was unquestionably a real book, I knew what he meant. When was I was going to write something taking place in the real world versus my imagined one? I could argue all day long, but I wouldn’t change his mind. The same for Deborah Roberts, I’m sure, who said, “The idea of anybody being an artist didn’t make sense to [my parents]. And it wasn’t because they were ignorant. They just didn’t understand.”

One of a parent’s duties is to raise their children to be able to take care of themselves—and to hopefully do so with more ease and resources than they managed to. To do that, you need money. To get the money, you need the degree(s) and a job. A good job. A real job. Their intentions, of course, are good. They’re historically good. In addition to writing about worlds that I make up, I’m also an oral historian. I sit with elders and ask questions about back-in-the-day. I also research those back-then happenings for further context. And for black people in colonized countries, education is like religion. It’s seen as a direct path to freedom.

It was illegal for us to be literate during slavery. Human traffickers feared that literate hostages would rebel or escape. Meanwhile, plantation owners sent their children off to college and they came back home and added more revenue to the family’s portfolio. After slavery ended, gaining an education was still difficult for black and poor folk, especially sharecroppers, because the family needed as many hands as possible to help in the fields. Meanwhile, the grandchildren of former plantation owners were coming home from college and adding more revenue to the family’s portfolio. Then there were the voting literacy tests, which were administered at the discretion of those in charge of the voter registration. You had 10 minutes to answer 30 questions and had to get ’em all right. If you failed, you couldn’t vote. And you’re hearing through the grapevine about how so and so down the road got their land taken because they signed a contract they couldn’t read. Meanwhile…you get the point.

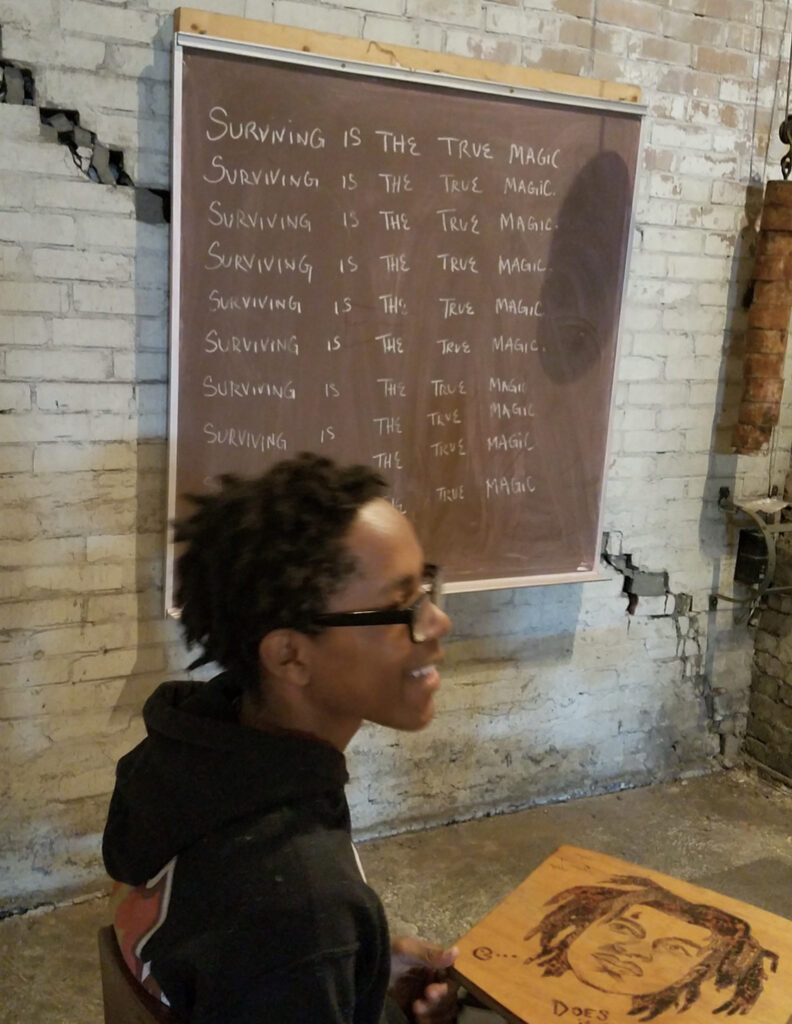

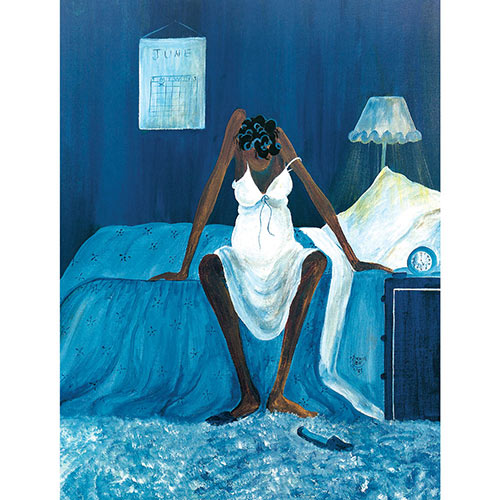

CJ named this performance piece “Stuck” (2017)

When Ms. Madie Underwood from Savannah and Philly told me how her parents were relegated to jobs that didn’t pay enough to cover their daily expenses, I understood even more why my parents and grandparents stressed getting an education. I understood why they hesitated when I explained that I was taking my son out of school to homeschool him. Ms. Madie’s story reminded me of my mother wishing that her mother, who didn’t go past elementary school because she was too busy sharecropping down in the delta, could’ve seen her graduate from college. I remember her saying how proud my grandmother would’ve been to see me walk across two university stages. That’s because education for black folk ain’t a shrugging matter. Historically, it determined where on the ladder our livelihoods rested.

Yet, times have been and still are changing. I saw a post on Facebook a few days ago asking readers to share a scam they fell for. Most people, of all races, replied “college.” It’s become so expensive that many folk couldn’t work and pay for it themselves if they wanted to. We get loans to get a degree to get a job that can (hopefully) afford to cover living expenses and repay the loans. A friend recently shared that from 2014 until today, she’s put over $20,000 towards student loans and the balance is up $30,000 since 2014.

- Studio Be in NOLA (2019)

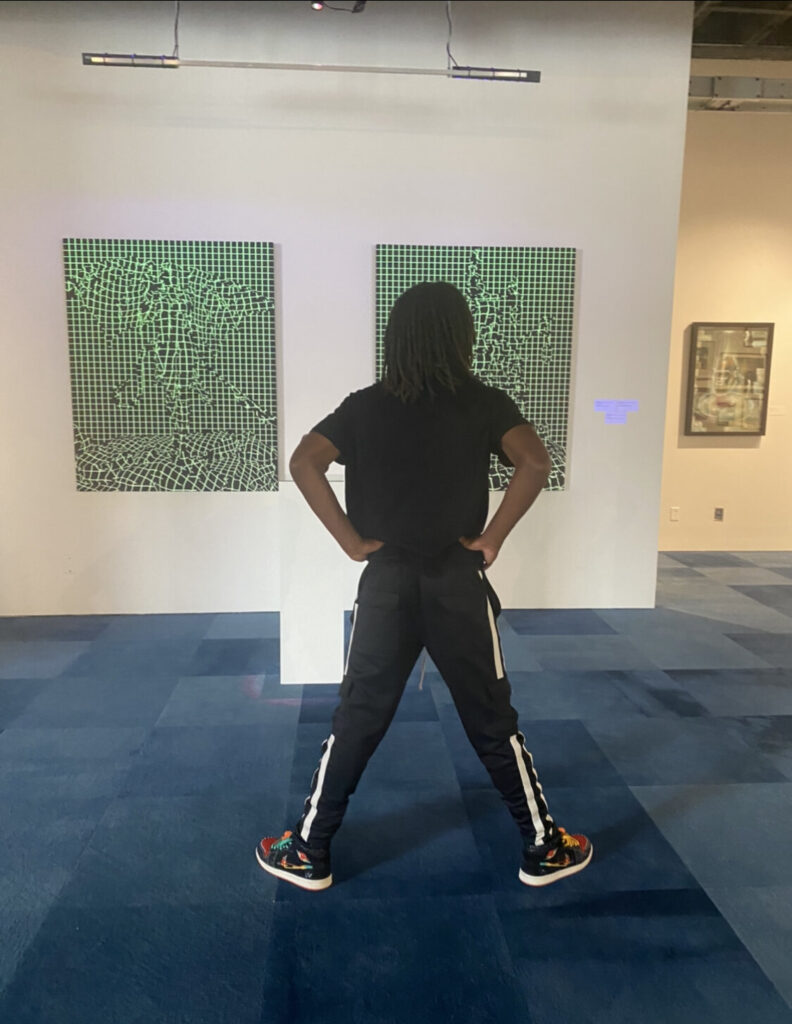

- SCAD’s Gutstein Gallery (2022)

That’s exactly what my sharecropping ancestors went through. Quoting Ms. Madie, “Whatever the sharecroppers needed through the year, they’d go [to the land owner’s general store] and get it and the white man kept a tab on whatever they needed and bought. At harvest time, when the white man have sold all of his goods and everybody settled for the winter, they always came out owing the white man money. There was never a profit. You always was in debt, so that debt would ride over into the next year. And naturally it’s another debt to grow on top of that debt, so, little by little, they owning you again like slaves.”

Mr. Curt Williams—from Vidalia and Savannah, Georgia—said, “It ain’t getting no betta. They just getting mo slicka.” Might as well love your degree, if you going into debt for it. Besides the money aspect, though, some of us just have different values. We’d rather risk being the struggling artist than the chief clerk at the railroad, struggling to get out of bed on a cold, Monday morning (word to Annie Lee). That ain’t a diss to careers that ain’t in the arts, just an example. There may be less black parents discouraging their children from an education/career in the arts these days, but hopefully less soon becomes none.

“Blue Monday” by Annie Lee (1985)