Black Hair Stylists ARE Black History

For making us look good, yeah, but for more reasons too.

They got the tea but not just for gossip.

I don’t know what it is about the chair, but something about it will get you talking. This is especially the case when you’re a loyal customer. Well, hair stylists would use that position to gather information. Instances where their clients were in positions of power made the tea even sweeter.

Born in or around 1801, Marie Laveau was not only New Orleans’ voodoo queen, but she was “a hairdresser” too. And she was often invited to the homes of some of the most powerful people in the city to fix their hair. She sipped a lot of tea up in there too. So when she came to ’em later with a request, well…it was hard to decline someone who knew so much.

I ain’t pretending to know how she did it, but it’s said that she even stopped a public execution once.

They used their salons as meeting places.

Churches and kitchens weren’t the only places where meetings went down. Funeral homes, barber shops, and hair salons were too. It was where you planned protests, made up your mind about who to vote into office, discussed the details of boycotts, planned bailouts, etc.

Madame Freeman was born in 1887 in Beaufort, South Carolina as Bridie Andres. (It was common for black women who were well off to call themselves Madame in those days.) She moved to Savannah and, in 1919, opened a beauty school on Alice and Montgomery. She supported the civil rights movement too. Issues in the community were discussed at her hair school and money was collected for bailouts and civil rights attorneys.

They funded businesses, schools, and other organizations.

Marjorie Stewart was born in 1896 in Monterey, Virginia. At 16 years old she moved to Chicago, graduated from a whites-only beauty school four years later, then opened a salon. Shortly after, she went back to hair school to learn how to style black folk’s hair (because what works for them don’t work for us). The second time around, she enrolled at Madam C. J. Walker’s beauty school in Chicago.

Within months of meeting Marjorie, Madam C.J. Walker promoted Marjorie as national spokesperson and one of her chief advisers. Marjorie also got cool with Mary McLeod Bethune, who, amongst so many things, founded Bethune-Cookman College, an HBCU in Daytona Beach which used to be just for black women. Over time, Marjorie raised thousands of dollars for the college and funded a new dorm. It’s named Joyner Hall to this day. (Joyner is her married name.)

According to Tiffany Gill in the Illinois Press, the frequent ads put in black-owned newspapers by black beauticians often kept the paper afloat during hard times.

They created jobs and generational wealth.

Madam C.J. Walker is the best example of this. Born in Delta, Louisiana in 1867 as Sarah Breedlove, she moved to St. Louis, Missouri when she was 20. After suffering from personal hair loss, she invented a line of hair products for black women. She eventually established Madame C.J. Walker Laboratories to manufacture cosmetics and train black folk in the art of sales. Once trained, they’d make presentations around their city or state to sell her products. This led to Madam C.J. Walker becoming one of the first women in this country with a self-made millionaire status.

Over the course of her career, she employed over 40,000 black women and men, and not just in the U.S. either. That’s major, especially for that time period. Black women without diplomas and degrees in those days often worked in white folks’ homes as maids, nannies, and cooks. Not only did Madam C.J. Walker give black folks’ jobs, but she also educated ’em.

After her passing, she left one-third of her estate to her daughter, Lelia, who ran the business with her. Lelia later added an A to her name, making it A’Lelia. Like her mother, A’Lelia was also a philanthropist, political activist, and patron of the arts. In fact, A’Lelia played a central role to the Harlem Renaissance.

She entertained writers and artists like Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, W.E.B DuBois, James Weldon Johnson, and more. They’d have private dinners, parties, and intellectual debates at A’Lelia’s inherited homes, including the 34-room Villa Lewaro. Safe spaces like the ones A’Lelia provided are important to creatives. Being able to kick back, dance, and exchange thoughts with other artists does wonders for our mental health and our creativity.

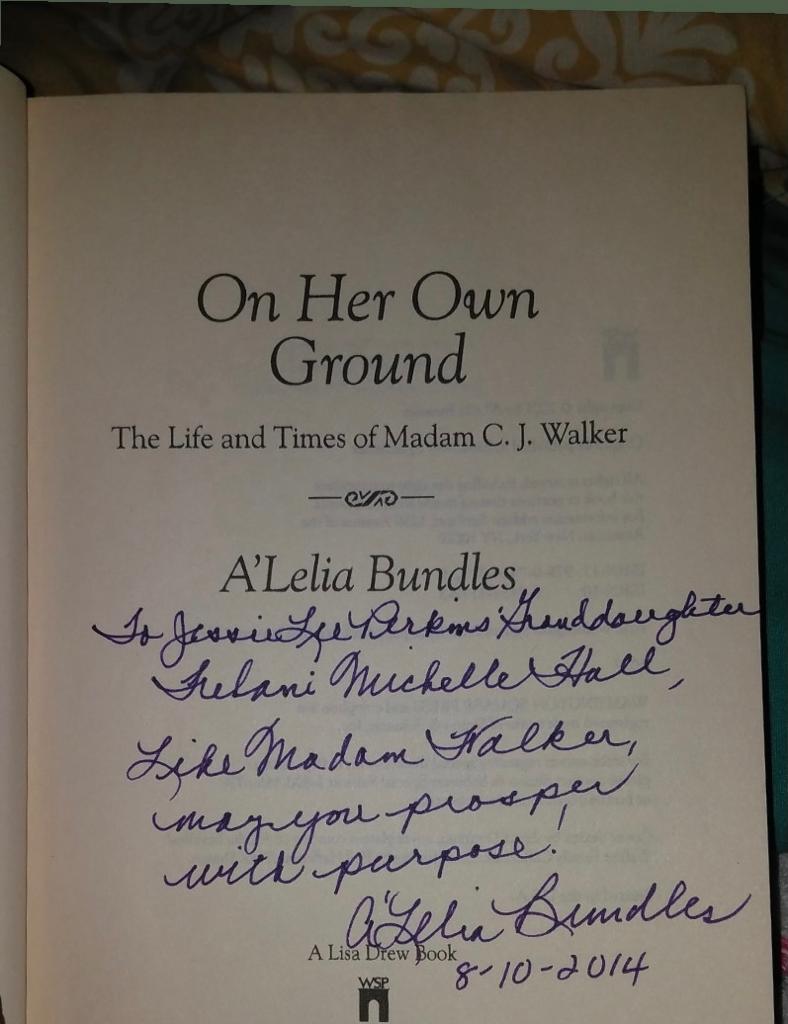

The lifestyle Madam C.J. Walker earned for herself and her family is a long way from her (literal) cotton-picking beginnings. So much more is now known about her life and her work because her great-great granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, wrote Madam C.J. Walker’s autobiography, titled On Her Own Ground, in 2001.

The title came from an excerpt of a speech that Walker gave at the National Negro Business League in 1912. She said: “I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there, I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.”

When we think about black history heroes, hair stylists don’t typically come to mind. We should change that though. Black hair stylists kept us (and still keep us) looking good, yeah, but they’re important to black history for so many more reasons.

If you like this post, you’ll love the book. Get yours. If you wanna keep content like this coming, make a one-time CashApp investment at $TrelaniMichelle, or become a monthly patron.