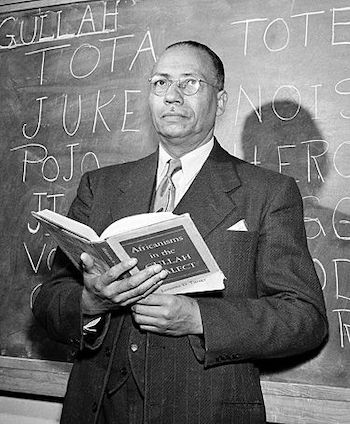

Lorenzo Dow Turner, The Father of Gullah Studies

Written by K.Nicole Parker

Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust was released in 1991 but set in 1921, depicting the struggle between those trying to preserve the old ways and the rich culture of the Gullah Geechee and those wanting to break ties with it and move North to assimilate in the midst of the Great Migration.

Though I was a military brat, my family has deeply southern roots. My mom’s side is from Allendale and Frogmore, South Carolina, and my dad’s side has origins in Alabama and Tennessee. I remember distinctly when I would use slang, act up, or do something that my parents thought lacked common sense or good judgement, my dad would call me a “doggone Geechee.”

At the time, I didn’t know what that meant, but the context with which it was used let me know that it wasn’t a good thing. It wasn’t until a few years ago, when I started researching my family lineage, that I actually found my Gullah Geechee roots and how it had been maligned by many in the community to denote being slow or tied to the old ways.

This is essentially what happened in 1929 when Lorenzo Dow Turner taught a summer program at South Carolina State University, an HBCU in Orangeburg, South Carolina. Before that, he taught at Howard in D.C. So imagine his reaction when he heard them Gullah Geechee students krakin teet at SCSU. In fact, he asked them what they were speaking and they replied, “We Gullah.”

Artist: Sabree’s Gallery

That response inspired Turner to learn more about the Gullah language. “His research focused on the Gullah/Geechee community in South Carolina and Georgia, whose speech was dismissed as ‘baby talk’ and ‘bad English.’ He confirmed, however, that quite to the contrary the Gullah spoke a Creole language and that they still possessed parts of the language and culture of their captive ancestors” (Smithsonian).

He studied many African languages (Ewe, Yoruba, Bambara, Wolof and Arabic) and linked them to Gullah. Words like cootah/turtle, oonah/you, nyam/eat, buckra/Caucasian, and benne/sesame are both African and Gullah (and, for many, Caribbean too). His studies helped prove that, despite how hell bent colonization and slavery was on killing African cultures, we were able to retain not only our customs but we were able to take our native tongues and morph them into a brand new dialect. Gullah is often confused with Jamaican Patois or Bahamian Creole when heard, but there are many similarities.

#WeAllCousins

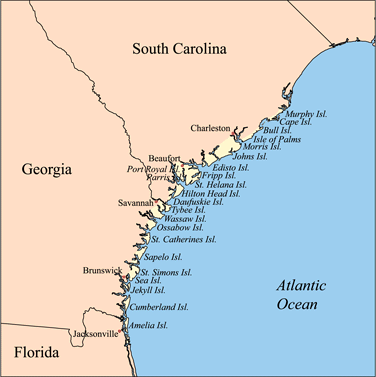

Turner went deep with his research too. After getting a grant from the American Council of Learned Societies, Lorenzo Dow Turner and his wife, Geneva, moved to the Sea Islands for over a year to more closely study the Gullah people and their language. He spent time in both the Georgia and the South Carolina Sea Islands—Harris Neck, Brewer’s Neck, Sapelo, St. Simon’s, Edisto, John, St. Helena, and Wadmalaw.

Today, Lorenzo Dow Turner is referred to as the Father of Gullah Studies. He was born in Elizabeth City, North Carolina—on the outskirts of what we now consider the Gullah Geechee corridor. He raised right outside of Washington D.C. though, which partly explains why he chose to get his first degree in English from Howard. Then he got his Master’s from Harvard and his PhD from the University of Chicago.

He taught at Howard for more than 10 years; then Fisk University, where he also designed their African Studies program; South Carolina State, which was the genesis of his Gullah studies; then Roosevelt University in Chicago, where he was the Chairman of the African Studies program. He published many books, including Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect, which was used as research for Krak Teet.

Turner’s research gives empirical evidence (information you get from either experimenting or observing versus just reading/hearing about it) of how resilient Black/African culture is. Somehow it keeps close to its origins, no matter who or what tries to erase it. Even today, if you look at Black communities in different regions, their differences and similarities in their speech have withstood the test of time. It also makes me think of the debates, namely in the school systems, about Ebonics (Ebony Phonics) or AAE (African American English) as it came to the forefront in the ‘90s.

He died on February 10, 1972 in Chicago at only 42 years old, but he did a lot in his time here. He was a game changer, who proved that it’s possible to study a community outside of your own and honor it without overstepping boundaries. He wasn’t the first to do it or the only one to do it, but he took his research to the academic world to say: Just because certain people ain’t trying to sound, look, or live like white folks don’t make ‘em wrong or backwards. It makes them true to who they are. It makes them walking history lessons.

The Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters

The Black community is in a state of remembering. There are Netflix specials such as High Off the Hog that highlight Gullah Geechee cuisine and social media personalities that are putting Gullah Geechee culture right in people’s faces. This appreciation for Gullah culture nods back to Turner’s research and positions it as the foundation that we draw upon as we open the eyes of our community. It brings the pride our elders didn’t see when they tried to separate us from it because they felt opportunities would come only if we erased this part of ourselves.

Lorenzo Dow Turner tells us that we are perfect as we are. Our nuances in language and culture are how we stay connected to our Ancestors of the South and our Ancestors of Africa. To know where we are going, we have to know where we have been. Turner’s work is another map that lets us know our linguistic nuances are guideposts that will always lead us home.