Are Quilts an Expression of Hoodoo?

Hoodoo is a set of beliefs and behaviors that are meant to protect you, heal you, guide you, and get your needs/desires met via the power of the spirit. Protection example: Enslaved folk sprinkling hot foot powder to cover their track when running away. Healing: Laying hands on someone who’s injured or ill. Guidance: Interpreting dreams, reading astrology, prophesying, tarot cards. Fulfillment: Cooking collards and some kinda legume (bean/pea) for the New Year.

I recently interviewed and wrote an article about Dr. Carolyn Mazloomi. She’s a quilter, which is what got me MORE interested in quilts. I have been for a while, went to a class before, and plan to make a quilt soon. But before I interview folk, I try to learn as much as I can about them (where they grew up, what kinda work they do, how/why they do it, etc.). Cannon-balled down the quilting rabbit hole, which is how I learned about Harriet Powers.

Harriet Powers

Ms. Powers was born enslaved on October 29th, 1837. She was freed after the Civil War, lived in Clarke County, Georgia most her life, and bought four acres and a farm with her husband to sustain themselves and their nine children. Ms. Powers didn’t work outside the home, but she did quilt. And she was GREAT at it. She made one that’s been retitled the Bible Quilt.

The Bible Quilt features 11 blocks and each block depicts different bible stories. Ms. Powers entered the quilt in the 1886 Athens Cotton Fair, which showcased arts and crafts from black and white folks. A globe-trotting teacher and art collector named Jennie Smith saw the quilt, fell in love with it, tracked Ms. Powers down and asked if she could buy it for $10 (that’s the equivalent of $240 today). Ms. Powers refused. She loved it too much!

I learned about this part of Ms. Powers’ story through Kyra Hicks, an African-American quilter who started researching and writing as something to do while unemployed and became a Harriet Powers scholar and biographer. Kyra said on a New Books in Art podcast that it’s even difficult for her to part ways with quilts she made and love.

That reminded me of Dr. Mazloomi warning artists not to sell everything, to save something for yourself and for your family.

Times were hard, taxes were high, and money wasn’t easy to come by in that part of the state. So Ms. Powers did what she had to do and reached back out to Jennie to see if she still wanted the quilt. Jennie only offered $5 this time though, but Mr. Powers said to gon’ sell it anyway. That broke my heart, so I know it hurt Ms. Powers.

Sometimes things be feeling like tragedies, but be working out in our highest favor.

Here’s why I say that: Ms. Powers also asked Jennie if she could come visit the quilt from time to time, and Jennie agreed. During those visits, Jennie would ask Ms. Powers about the quilt and she’d record the details. As Kyra said, “That documentation survived along with the quilt.” Documentation exponentially increases the value of art, especially after the artist passes away. The quilt is now in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

It goes deeper: Jennie exhibited the quilt at the 1895 Atlanta Cotton Exposition (Booker T. Washington delivered his famous Atlanta Compromise speech here). Women from Atlanta University commissioned Ms. Powers to make a quilt for a board member, and she did. That quilt is now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. And those are the only two quilts that we know of that was made by Harriet Powers and still exists today. Because of those surviving quilts and the documentation to go with it, we know even more about our people, what they valued, and how they spent their time. It’s why Harriet Powers is now known as the Mother of African American Quilting.

Quilts protected and guided enslaved folk who had runaway.

“According to legend, a safe house along the Underground Railroad was often indicated by a quilt hanging from a clothesline or windowsill. These quilts were embedded with a kind of code, so that by reading the shapes and motifs sewn into the design, an enslaved person on the run could know the area’s immediate dangers or even where to head next.” —Smithsonian Center for Folklife

Here in Savannah, First African Baptist Church served as a safe house for refugees of enslavement. It’s one of the oldest continuously operating African-American churches in this country, having started in 1773. The ceiling the church models a Nine Patch Quilt, which were often the kinds of quilts that folk hung from clotheslines and windowsills to let folk know where to go or what to watch out for.

Quilts are healing too.

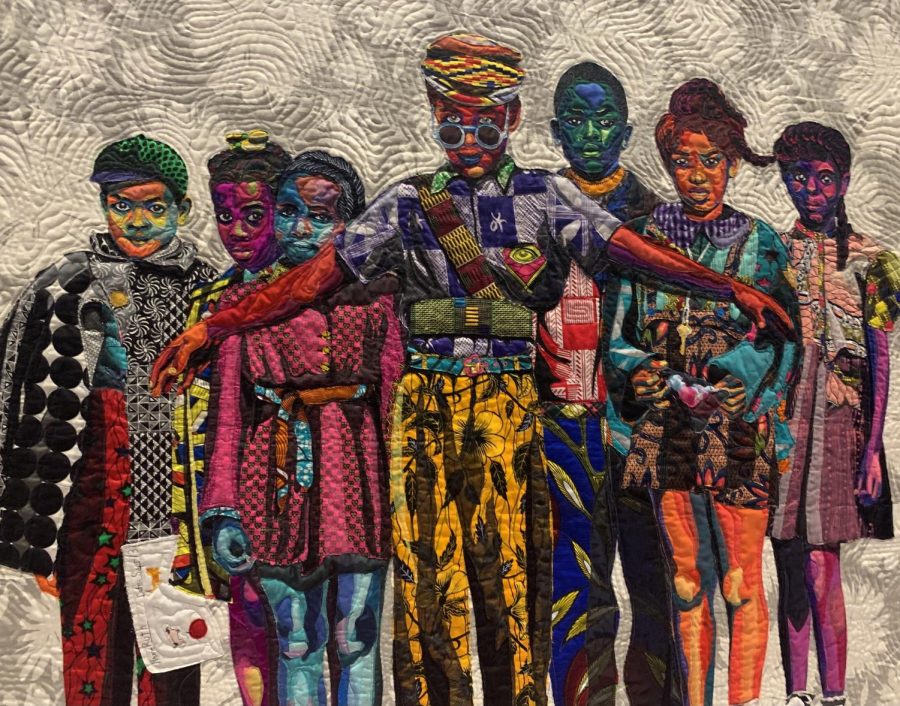

Every time I see a handmade quilt, I wanna hug it. I know the time and effort it takes to make one. I know the creativity, skill, and intention in every single layer and stitch. I understand why so many families pass them down through the generations (and wish mine did). I see it the same way I do making a stew or a gumbo. It’s warm, comforting, and loving. I’m reminded of one of my favorite books, The Hand I Fan With, where the main character, Lena McPherson, climbs into bed after experiencing heartbreak and pulls the heavy quilt made by her grandmother up over her shoulders. Quilts are healing too. (That’s Wendy Kendrick in the pic.)

And quilts fulfill the need to be warm while telling a story.

As Dr. Mazloomi said best, “Every quilt tells a story, even those patchwork quilts that you see. Don’t think just because you’re seeing little geometric pieces that the quilts don’t tell a story. Every time a maker puts hand and needle to cloth, it’s a story…Hundreds of years from now, people will be studying these quilts.”

Given the nature of hoodoo and its purpose, it’s clear that quilts serve as a profound expression of this ancient tradition, which supported a people who were never expected to make it—yet continue to do just that: survive.

…Right?

This is a beautiful article! Quilts are indeed a hug.

I like how you called the UGRR quilts a legend. Though quilt historians eschew the possibility of this, I believe there could be a bit of truth to the use of quilts as messengers. We come from people whose ancestors have a long history of embedding meaning in cloth through mark making, applique and stitching. In addition to every patchwork telling a story as Dr. Mazloomi states, random marks and patterns may also tell a story – or give direction.

Thank you for mentioning the importance of documenting quilts and quilters and Dr. Mazloomi’s advice cautioning quilters not to sell everything.

Your work is SO important and heart centering. Thank you!