We All Had a Black Wall Street

There’s a running joke that if you want to know where any city’s ghetto is, just find Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd.

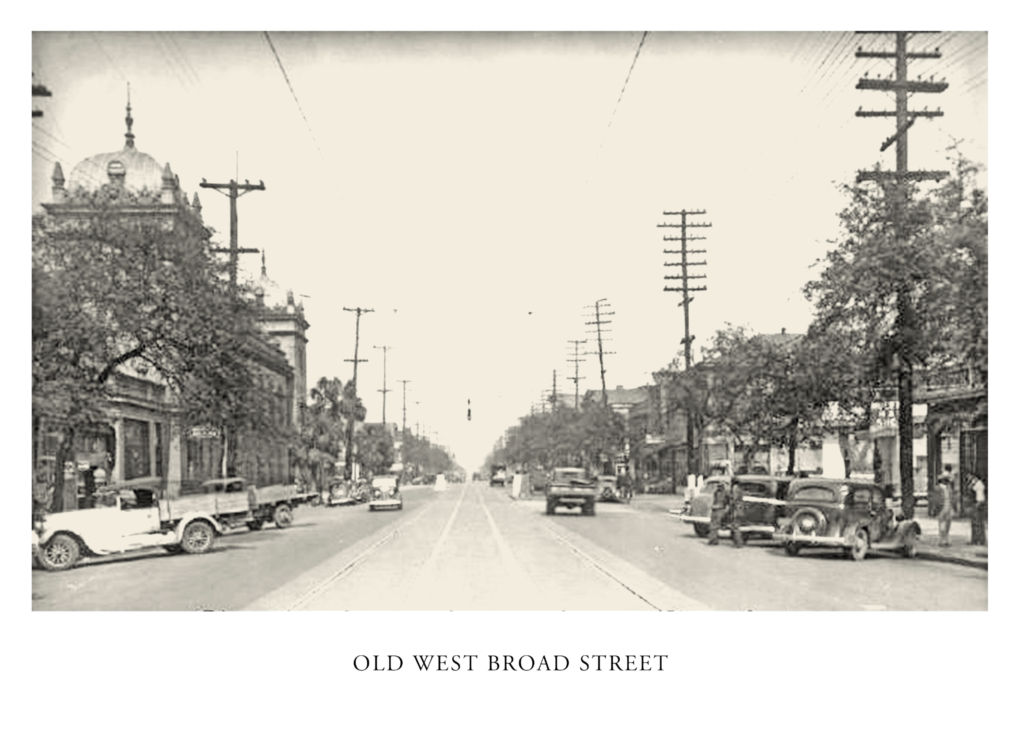

But that wasn’t always the case in Savannah. MLK, extending from Bay Street to Exchange Street, was once a corridor of thriving black neighborhoods and businesses called West Broad Street. It was our black Wall Street. There was even a black-owned bank, originally called the Wage Earners Bank. Opened in 1914, it was one of the most gainful banks owned and operated by persons of color in the country by 1920, with customers in almost every state making deposits. It was also the first black bank to accumulate over $1M in assets. W.E.B. DuBois, in his Crises Magazine, said it helped more Negro business ventures to success than any other Negro bank.

West Broad Street reflected community.

Sticking together wasn’t limited to opening your doors to family members or looking out for your neighbor’s children. It was also supporting one another’s entrepreneurial endeavors. Black people gave each other places of community, yes, but also safety and economic support.

We usually read about the togetherness of black folk during this era and compare it to how far off we are from that today. It’s important to understand, though, that unity in those days was damn near not an option. Either you couldn’t shop with white businesses at all, or you weren’t respected there.

“Businesses on West Broad Street were places were black people could spend their money with dignity, which was not always the case on Broughton Street, the busy promenade where blacks often were not allowed to work behind the counter, or try on hats before they bought them, or have change put in our hands instead of dropped on the counter. On Broughton Street, black people couldn’t eat at lunch counters our expect respect for the dollars we spent. West Broad Street was thus our world.” —Coming Full Circle: From Jim Crow to Journalism

Every city had a black Wall Street.

The cities with a bunch of black folk in it, that is. And most of them ended the same way too. But before we get into that, here’s a list of names for the black Wall Street in other cities:

- Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa

- Clairborne Avenue in New Orleans

- Water Street in Columbus, OH

- Seventh Street in Oakland

- Parrish Street in Durham

- U Street in DC

- Rondo Avenue in St. Paul, MN

- Ninth Street in Chattanooga

- Avenue G in Miami

- Florida Avenue in Jacksonville

- Hastings Street in Detroit

- East 12th Street in Austin

Most of ’em ended the same way.

An interstate cut through the Main Street, displacing the homes and businesses. In 1963, in Savannah, residents and entrepreneurs on West Broad Street were ordered to leave by the City of Savannah for the construction of I-16 and the housing projects, Kayton and Frazier Homes. Although the interstate arrived in the ’60s and immediately uprooted many residents, the businesses didn’t leave as quickly. They hung around for another 25 years or so. Today, of all those businesses on Savannah’s black Wall Street, only one of them from those days still remains on the same street.

Stopping new highway expansions

Know your history lest it repeats itself. Ain’t that what they say? Just as every city had a black Wall Street and most of ’em suffered the same fate, there was always a group resisting the interstate and suggesting where else it could be placed. The struggling seemingly doesn’t end, because many cities are right back where they started. Take Houston, for instance.

Even as communities grapple with how to reverse the injustices created by highways, others are fighting plans to expand and build new ones that activists say will impose many of the same harms. A $7 billion plan in Houston would add 24 miles of freeway along I-45 as well as I-10 and I-610, and displace more than 1,300 homes, businesses, schools and places of worship. But grassroots and civic organizations have opposed the state project for years, and the city has offered an alternative plan to repair the highway without expanding it, while investing in transit and pedestrian connections instead. Recently, federal officials intervened in an early sign of how the Biden administration might handle highway projects poised to repeat mistakes of the past. — “What It Looks Like to Reconnect Black Communities Torn Apart by Highways”

Why we need to know dis

“Ain’t nothing new under the sun.” Ain’t they say that? Well, the problems we encounter ain’t necessarily new and the approaches to those problems might not be new, but the technologies are. Take social media and e-commerce, for instance. We’ve always had a means of getting in touch with each other and creating marketplaces, but doing it as fast and far-reaching as the internet is new.

We can’t stop change. According to Octavia Butler, God is Change. It’s inevitable, but you can be in relationship with Change. Get to know it through history. So if this has happened and continues to happen to our brick and mortar spaces, how might it happen to the digital spaces we’ve created to connect with each other and circulate our coins? How can we get ahead of the problem?

If you know folk who are already on top of these questions, please comment below. And if I left off your city’s historical black Wall Street, add that in the comments too.

Much love to our new and recurring monthly patrons:

Jessi, June Johnson, Yolanda Acree, Cala, D. Amari Jackson, Yvonne Carter, Black Art in America, Nakia Morgan, Yeseree’ Robinson, Akeem Scott, Rosa Bennett, Dee George, Add your name here

Your monthly contributions allow us to pay black writers and artists, and get more creative and consistent in the content we deliver. We put a lot of time, love, and money into researching, writing, and sharing. Click here to learn more.