John Langston Gwaltney: Your Life Purpose Requires Your Abilities, Disabilities, and Life Experiences

…Soji is the word for an unbaptised person in the old-time religion. Such unbaptized persons learned the core Black way by listening to their elders. And the other thing that those people had to pledge to do was to follow the truth wherever it leads you. That’s what native anthropology has to do. And that’s a sort of simple statement of a very difficult mission, because if you follow the truth wherever it leads you, you will have difficulty in this world with publishers, with universities, and occasionally with your own constituents… –John Langston Gwaltney

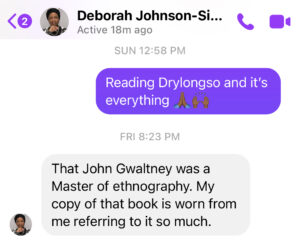

Just like I have categories of friends, I also have categories of elders. I have those I talk to every blue moon and I have those I talk to every week. Ms. Pat is one of my every week elders. (Dr. Pat to y’all though.) She recommends books for me ALL THE TIME. I just buy ’em and get to ’em when I can. One of the books she suggested more than three times was Drylongso.

Now, I’m always reading three books at a time. Rarely do I finish ’em these days. Drylongso grabbed me from the first page though. And when a book (or a movie) is REAL good, I gotta pause and see who created it.

It takes a village to raise a child

John Langston Gwaltney was born in Orange, New Jersey on September 25, 1928. The same year my grandmother and Vera Mae Green were born–one year before the Great Depression started. His dad was in the Navy and spent most of his life touring the world. The stories he’d bring back home planted a deep curiosity in his children about the different people and cultures across the globe.

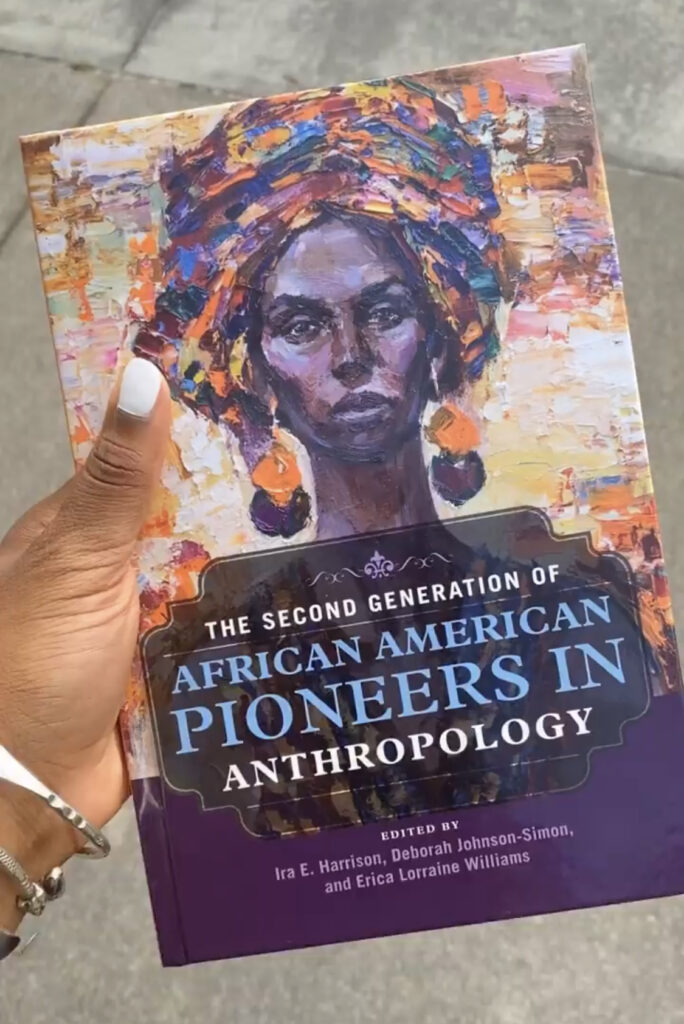

At two months, John went blind and never regained his eyesight. In The Second Generation of African American Pioneers in Anthropology, one of my elder-friends Dr. Deborah Johnson-Simon wrote a chapter about John Langston Gwaltney. She wrote about how John’s mama tried everything to help her son get his eyesight back, but nothing helped. Once they realized it was something he’d have to live with, she went above and beyond to expose him to different talents that wouldn’t be hindered by his disability.

One that stuck was wood carving. He said he wanted to try it and his mama brought him a piece of wood and a file and said, “now let’s see what you can do.” Whatever he produced was enough for her to call her uncle, who was a wood carver in Virginia, and get him to train John.

Pushed way outta his comfort zone

His mama also made him do stuff that scared him–like summer camp. He dreaded it, fearing his blindness would make him a victim, but she made him do it. He ended up loving it and wanting to go back every year! I’m sure that played a role in him later going to Mexico to do fieldwork. (Fieldwork = interviewing the people and studying their culture in person.)

The project was the study of blindness in the Indians who lived in the village of San Padro Yolox in southwestern Mexico. The village was not accessible by vehicle and the inhabitants spoke the ancient tongues of their Chinantec ancestors, not Spanish. The village was set in an area with rough terrain, steep hills, valleys, and drastic climate changes.

Having done his research on the area early on, he knew he needed a few more skills under his belt. He needed to walk or ride a horse to the village and other places he wanted to go. He took horseback riding lessons and had some extra strong metal canes made to take along.

His yearlong study focused on how the village maintained its social order when so many of its members were blind. With a grant from the National Institutes of Health, he had almost all of his expenses covered. —National Federation of the Blind

San Pedro Yolox Oaxaca

When the student is ready, the teacher appears

Well, John first heard Margaret Mead talking about her work as an anthropologist on a radio show called School of the Air. It grabbed his attention. In 1959, he enrolled at Columbia University in New York. Guess who was one of his instructors? Margaret Mead. In addition to being his professor, she also became a mentor and helped him prepare for his fieldwork in Mexico.

John Langston Gwaltney wrote a self-portrait of black culture

John Langston Gwaltney earned a PhD, married, had two children, carved wooden canes, taught, and wrote several books, including Drylongso. He published Drylongso in 1980 to create a self-portrait of “core black culture” in America. Just like I did with Krak Teet, Gwaltney went straight to the people. The everyday, ordinary people.

“What does it mean to be black?” Because the book includes their actual response to this question, it’s an oral history. Gwaltney ain’t telling us what they said. We’re reading what they said, exactly how they said it. That’s why I love oral history. It’s stories straight from the horse’s mouth.

Your Life Purpose Requires Your Abilities, Disabilities, and Life Experiences

Doing the kind of work we do requires a certain personality and skillset. People have to be able to trust you–quickly! I joke often that everyone tells me their secrets and have done it all my life. It’s true though. So your spirit gotta be right. And you gotta know how to ask the right questions and know when to speak and when to let the silence take up space. You gotta be vulnerable in your curiosity and ignorance without being an annoyance. As a child, you were probably already super interested in the different places and people around the world. This kinda work is heavy on the soft skills.

But can you do that blind though?

John Langston Gwaltney proved you can. In Drylongso, one of the women he interviewed, Carolyn Chase, said: “I’ve tried to tell you the whole truth and I’ve told you things I’ve never told anyone before. You may find it hard to believe, but I am not normally a very talkative person…. I started not to talk to you at all. And quite frankly, if you had not been blind, I don’t think I would have.”

Ms. Carolyn might’ve been the only one to admit it, but I’m sure more thought this way too. His blindness was a superpower, in this way. It made folk comfortable enough to put their guard down.

All of it made him the game-changing anthropologist that he was: his natural skills, his blindness, his mama writing a letter to Eleanor Roosevelt to get him in a good school, his mama pushing him outta his comfort zone, his daddy sharing stories from overseas, his uncle teaching him the ancient art of wood carving, his grandfather teaching him about the Hausa people, his sister teaching him how to make cheese biscuits…it all served his life purpose.