The Great Migration: When Black Folks Left the South

by Diamond Afeni

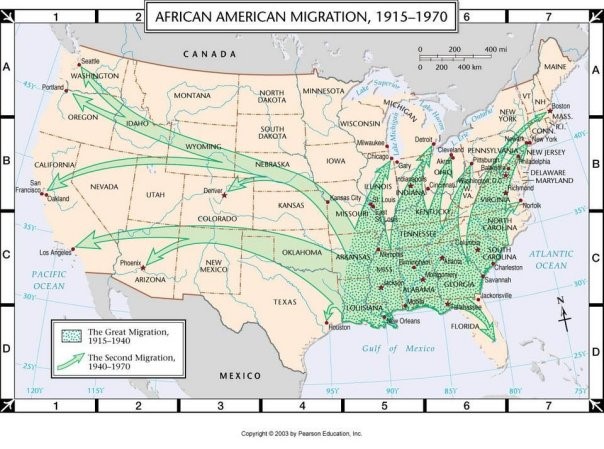

Beside the slave trade, black peoples’ largest migration in this country began in the mid 1915s and ended in the 1970s. Before that, according to the United States Census of 1910, more than 90% of black people lived in the South. The great migration of black folk from the southern states of Georgia, Louisiana, Florida, Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and the Carolinas spread this percentage out.

Isabel Wilkerson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning blackwomanwriter from DC, did a deep study of what’s come to be called the Great Migration. A lot of my research came from her book, The Warmth of Other Suns.

Her research suggests that an estimated 6 million Black people (more or less) migrated to different corners of the United States of America after World War I. This included cities like Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, New York, and California.

Many factors contributed to the Great Migration.

The weather might be warm in the South, but the social climate was cold af. You had Jim Crow laws, for example. And, as we know, being separate wasn’t the issue. Being separate and less than was the real issue. Our elders and ancestors wouldn’t have fought for integration if our schools, neighborhoods, and public facilities were equally up to par.

On top of that, black people faced ongoing violence. We’ve all seen the pictures and film clips of police siccing dogs on us and blasting us with high-pressure water hoses for fighting for our rights. Cities like Tulsa, however, proved that we could be minding our own black business and they’d still reign terror on us. Not only were adults’ lives at risk, but children’s were too. So, though born and raised in the South, many black southerners were ready to go.

World War I created a drastic need for labor. This high demand for industrial workers gave many black families a chance to leave the South and make more money up North. Society was moving away from making most of its money on farms and beginning to make it in factories. Furthermore, money made on farms wasn’t as consistent as a paycheck.

Leaving wasn’t always a walk in the park.

Remember: After slavery, many black folk in the South became sharecroppers. Even though slavery was over, the fields still needed to be worked. There was supposed to be an agreement as to how much the landowner would get from the harvests and how much the black folk would be paid. Many times, sharecroppers would NOT be paid. If they lived on the land, their rent was deducted. Used the land owners tools and mules? That was deducted. If the landowner had to provide clothing or food, that was also deducted. Instead of being paid, sharecroppers were often in debt. And the debt got bigger over time.

This wasn’t the case for everyone. Mr. Johnnie Parrish from Krak Teet, for instance, said his family made real good money as sharecroppers.

The great migration left many southern landowners without field hands, which ultimately impoverished a lot of ‘em. If ain’t nobody working the land, ain’t no crops being planted, harvested, or sold. They were mad about that, so they created laws that made it harder to leave. In many states, for example, it was illegal for sharecroppers to move if they had a debt with the landowner. They also terrorized us for leaving.

“In Albany, Georgia, the police tore up the tickets of colored passengers as they stood waiting to board…A minister in South Carolina, having seen his parishioners off, was arrested at the station on the charge of helping colored people get out. In Savannah, Georgia, the police arrested every colored person at the station regardless of where he or she was going.” —The Warmth of Other Suns

That’s why we’d sneak away. (I wonder if this is where the phrase “move in silence” came from.)

Our final destination was usually one of the stops on the train route. That’s why people from Georgia and the Carolinas have family in Philly, Jersey, and/or New York. And why folk in Texas, Louisiana, and Alabama have people in Cali, Chicago, and Ohio.

The North wasn’t the promised land we thought it would be though.

It was a trying time for us (and still is). Although segregation was illegal in northern states, black people weren’t exempt from racism and prejudices on the job, in the housing markets, in the schools, etc. These very issues led to what some called “self-contained neighborhoods” (they were more often called “ghettos” or, these days, “projects/hoods”) and a significant wage gap between black and white families. So when houses and land increased but wages for black people remained the same, it made it harder for us to not only get ahead but stay afloat.

In part 2, you’ll learn about how policies during The Great Migration created systematic issues (for better and worse). Make sure you’re subscribed to our newsletter, if you ain’t already.